Peter Graber’s self-described 65-year relationship with Camp involves years as “camp brat and child laborer” (1959-69), “staff member” (1970, 1972-76), and “volunteer and adult camper” (1977-2025). He shares the following reflection as part of our honoring of Camp Friedenswald’s 75th anniversary.

Given my sixty-five years of history with Camp Friedenswald, there are many stories that I could tell. Some of them might even be mostly true. Given the times we live in today (Spring 2025), I decided to highlight an aspect of camp’s history that not many may know about, the camp’s relationship to its local community, particularly the African-American community. I do this as a very white participant in this story. I can’t speak for my African-American brothers and sisters. I hope that we are able to hear their voices as well in the future. As you read, please remember that my involvement post-1975 has been as a volunteer and attendee, so my understanding of these years may be lacking. I welcome other perspectives and/or corrections.

As the leaders of Central District Conference (CDC) were looking for a place to locate their summer camping ministry, they considered the natural aspects of the land as well as its location in relation to the geography of the conference churches. I don’t believe that much thought was given to the particular political and social environment around the camp. My parents, Dan and Mary (Marge) Graber, were the first camp staff to live on the grounds of the camp. Our family moved there in 1959 when I was four years old. We lived in the apartment at the back of “Tubby’s Store” which was remodeled to create the “Friedenswald Lodge,” This was the location of winter camping at Friedenswald until 1967 when the main camp dining hall was expanded and insulated for winter use.

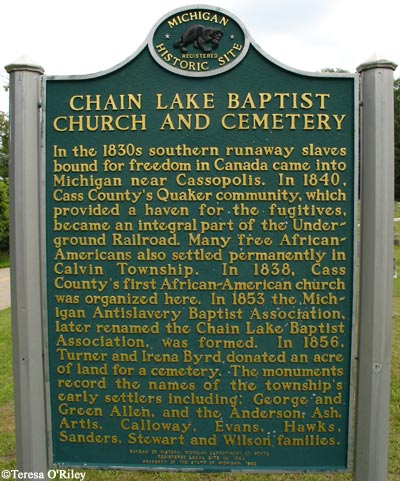

This apartment where I grew up was on the corner of Union Road and Peninsula Drive which was in the Vandalia, Mich. school district and Calvin township of Cass County, Michigan. This is significant because it meant that we attended the Vandalia (and later Cassopolis) public schools. The Cassopolis schools, and particularly Calvin Township, had a large African-American population. In some years, we were the only white family on our bus route. In Calvin Township, there was a long history of local African-American leadership, farming, and business ownership. For a period, Cass County had the largest percentage of African-American farm ownership outside the South.

Because the camp was unable to pay a salary to the early staff members, my father, Dan, worked as a school teacher and later school social worker in the Cassopolis Public Schools and our family related to the local community, including the African-American Baptist church half a mile away from our home. The pastor was Boston Dyes, and his son, Dwight (Skip) Dyes later served on the camp staff along with other local young adults. Dyes still lives in the community and was a County Commissioner for Cass County for many years.

Our family relationships were mostly with other local families and our childhood friendships were with the children in our “neighborhood.” Our Mennonite friends were people we saw in church or once a year at camp in the summer. It also meant that most of our friends were African-American. This does not mean that I understood the racist environment in which I lived. In later years, I talked with an African-American friend about riding my bike to school in Cassopolis, 10 miles away. He noted that this was not possible for him because it was too dangerous for him to ride a bike through the Diamond Lake area, known (to him) for its racial violence.

In 1968, under the new director, Jess Kauffman, the camp developed a cooperative relationship with local community leaders to host what was called “community camp” in which children from the local area were able to enjoy the benefits of a week at camp. The children were a much more diverse group than the CDC young people, largely from lower income families and more than half African-American. In addition to giving these children a great camping experience, it provided a cross-cultural learning opportunity for the camp staff who largely came from rural and suburban white communities. Care was taken to orient the staff and to respect the culture and habits of the campers which were new to the staff members.

Remember that this was the late 1950’s and 1960’s when segregation was still legal and integration was not favored by all Mennonites. During these years, camp leadership also reached out to congregations with significant African-American membership to make sure they were welcomed into participation in camp programs. Woodlawn Mennonite Church on the south side of Chicago was particularly active in sending young people to camp.

Efforts were also made to create more racial diversity in the camp staff in these early years. This was difficult because the primary recruiting field for staff members was Mennonite colleges and these student populations were almost entirely white. Still, there were some Mennonite people of color who were recruited to serve on the staff, and some young people from local African-American churches. Some staff members were “alumni” of the community camps.

As permanent staff housing moved closer to the main camp, resident children attended the Constantine Public Schools, farther away and much more racially homogenous (white). Later efforts to develop relationships with the “local” community centered on the people who lived on the Shavehead Lake peninsula next to the camp rather than the Calvin Township, Vandalia, and Cassopolis communities. This was a real loss to the camp as there was less contact with a more racially and ethnically diverse population.

Since the early 1970’s, the camp has followed the course of most Mennonite institutions and focused on building cross-cultural relationships through international contacts and immigrants rather than with the African-American community. The area surrounding Camp Friedenswald has a rich history of indigenous and African-American inhabitants and many local people with stories to tell. All of this could be a resource for future camp programming. I know that intentions have always been good at Camp Friedenswald. We wait to see how those intentions will serve to enable stronger relationships with African-American’s locally and within the CDC.