As nighttime temperatures dip below zero and daytime temperatures barely climb into double digits, staying warm is a top priority for most of us creatures, human and non-human alike. We feed our bodies extra fuel to keep the furnace hot, and seek small spaces we can fill with heat. Look up from almost anywhere at Camp, and defoliated trees reveal the pockets of shelter where certain ubiquitous, often notorious, critters find refuge during winter months. Sit in a quiet house some morning, and you might hear them skittering around above your head, thieving your attic insulation or enjoying the heat while you sip your coffee.

Squirrels are the monkey-rodent of North America, and they delight, irritate, and disgust us. They race and leap through the canopy, defying gravity, filling the air with chatter, chasing each other in nauseating spirals around tree trunks. They sneak pet food from garages, and thinly disguise their rodenthood with flamboyant tails. What bird feeder hasn’t been plundered by squirrels? Who has not stood flabbergasted and peeved as furry, determined acrobats conquered impossible obstacles to access the cache of seed or suet?

Humans and squirrels have shared space and resources for thousands of years, and our feelings toward this monkey-rodent have been divided for just as long. In Norse mythology the squirrel Ratatoskr is a cosmic trouble maker who scampers up and down the tree of life, delivering messages tweaked to incite conflict between the tree’s upper realms and its depths. According to Navajo legend, though, humans have the squirrel to thank for our comfortable existence: It was the squirrel who first brought us fire. According to the Karok Indians, too, the squirrel brought fire to the human world, its tail curled for ever after from the heat.

Squirrels are familiar to pretty much everyone, so it’s easy to overlook how amazing they are. They’re found on five different continents, which means they’re incredibly adaptable to different climates; eight species are found in Michigan. Several species are common at Camp, and with a little practice you can tell who’s who.

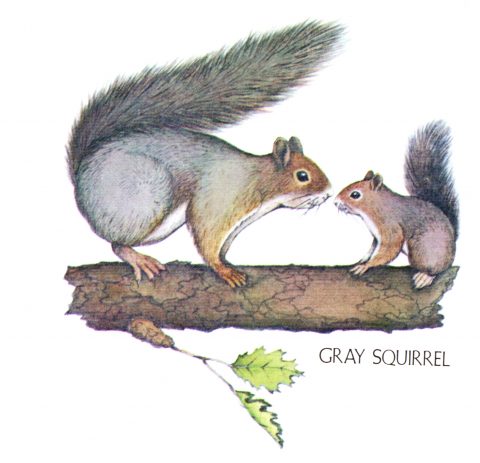

Gray squirrels prefer dense stands of hardwood and conifer trees, are least social of the tree squirrels, and might live most of their life around a single tree. They’re also attracted to river bottoms, which makes much of Camp ideal gray squirrel habitat. While you’re out in the woods watch for black squirrels, a beautiful phase of the gray squirrel.

Fox squirrels are bigger than gray squirrels, with their orange belly and rust-tipped tail hairs reminding us of the squirrel as fire-bringer. Look for fox squirrels around prairies that are adjacent to forests, and watch as they carefully stockpile nuts every year. Researchers have found that eastern fox squirrels not only stockpile 3,000 to 10,000 nuts each year, but also organize them by variety, quality, and preference.

The red squirrel’s ear tufts lend the rodent a look that is distinguished and laughable; molting the tufts once a year keeps them looking fabulous. Tufts, white belly, and white eye rings make red squirrels easily identifiable, but their small size can make them inconspicuous, especially when trees aren’t bare.

Most elusive is the nocturnal flying squirrel, but the southern flying squirrel thrives in the lower peninsula, even inhabiting suburban areas. If you’re on a night hike with Camp staff, watch carefully for squirrels leaping and gliding up to 295 feet from tree to tree. These endearingly big-eyed critters don’t hibernate during winter but may share a nest with other flying squirrels for extra body warmth.

So the Big Question is: Is Ratatoskr still running up and down the tree of life, inciting conflicting opinions about his descendants? What’s your reaction when a squirrel comes calling? Do you welcome it with gifts of corn and turn the other ear as it scurries above your ceiling? Do you combat feeder-raiders with deterrent mechanisms or the family dog? Say it is indeed thanks to squirrels that we have fire for heat and food; we then owe them at least tolerance. Is the actual Big Question how we coexist with a sometimes-nuisance? We may not be ready to consider the squirrel noble, but maybe we can consider the squirrel’s incredible monkey-like antics as periodic payment for bird seed and attic heat.

References:

Chamberlain, A. F. (1896). American Indian legends and beliefs about the squirrel and the chipmunk. The Journal of American Folklore, 9 (32). 48-50. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/532994.pdf

Geller. (2017). Ratatoskr. In Norse. Retrieved from http://mythology.net/norse/norse-creatures/ratatoskr/

McLendon, R. (2017, August 10). A few interesting facts about flying squirrels. In Mother Nature Network. Retrieved from https://www.mnn.com/earth-matters/animals/blogs/flying-squirrel-facts

Pierre-Louis, K. (2017, September 14). Squirrels are so organized its nuts. In Popular Science. Retrieved from https://www.popsci.com/squirrels-organized

Private Land Partnerships. (2017 accessed). Squirrels. In Part VIII species management. Retrieved from MI DNR: http://www.michigandnr.com/publications/pdfs/huntingwildlifehabitat/Landowners_Guide/Resource_Dir/Acrobat/Squirrels.PDF

Wild Birds Unlimited. (2009). How many species of squirrels are in Michigan? In Question of the week. Retrieved from http://lansingwbu.blogspot.com/2009/02/question-of-week-how-many-species-of.html